Due to the sensitive nature of the subject matter, we strongly advise teacher viewing before watching with your pupils. Careful preparation should be undertaken to prepare pupils before playing them this potentially traumatic and triggering story. The film includes descriptions of the racism black children and their families experienced in Britain, as well as the scientific racism that influenced policies such as segregating children in ESN schools.

SHANEQUA PARIS:So, this passport, this is my nan's passport. So, this is when she came to England in 1956.

I'm Shanequa Paris. These are photos of my grandma. She was born and raised in Alexandria, a town in Jamaica, but then came to Britain in 1956 to work as a dressmaker. There are thousands of us with parents or grandparents who came to Britain from the West Indies.

Between 1948 and 1973, nearly half a million people travelled from the Caribbean to the UK. Although black people have lived in Britain for centuries, many more moved here after the Second World War. They were British citizens, with British passports, many responding to job adverts for factories, the NHS and public transport. They have more recently become known as the 'Windrush Generation' after a ship called The Empire Windrush which took people from the Caribbean to London in 1948.

Some parents came over to Britain with their children. But by the 1960s, when this story begins, there was also a growing generation of black British children born in the UK. Their parents faced many difficulties in Britain, and were often only able to get difficult, low-paying jobs. But they were still optimistic that their children, being born here, would have a brighter future.

GUS JOHN:Generally speaking, Caribbean parents saw education and schooling as a route to social mobility. We came here, not to make loads of money, but to ensure that our children could get a better start in life.

SHANEQUA PARIS:But, unfortunately, this wasn't how things turned out.

In the '60s when British schools began to have more and more black children, some white parents started to object. They believed that having black pupils in schools would hold back the education of white children.

And the government agreed. In 1965, the Department of Education recommended only 30% of pupils should come from an immigrant background. To achieve this, black and Asian children were bussed out of their own neighbourhoods, so that they could be spread out across different schools.

DAVID DIMBLEBY:Good evening. Our main guest tonight is Professor Eysenck.

SHANEQUA PARIS:Eysenck, a leading psychiatrist of the time, believed that certain races were not as intelligent as others. This kind of scientific racism was used to justify treating black children as less intelligent, subhuman even.

JOHN EYSENCK:We give the same kind of education using the same methods with bright and dull children, this is not fair to either.

SHANEQUA PARIS:The belief that black children were somehow less intelligent than white children would have a dreadful impact. For one child, a visit to the dentist led to a decision that changed his life almost overnight.

NOEL GORDON:I must have been about five, six, maybe. I went to hospital because I had a problem with my teeth. And my mum took me thereand they said, "We're going to take them all out," because they were baby teeth. I woke up in a bed, and there was four doctors holding me down. I had a drip my arm.

SHANEQUA PARIS:During his dental operation, it was discovered that Noel had sickle cell anemia, a serious and dangerous blood condition. His parents were told that he needed to be sent to a state boarding school which could take proper care of him. But nobody explained what sort of school this would be, and that, in fact, his medical condition wasn't something that the school specialised in at all. While there, Noel noticed that the children at the school had conditions that were very different to his, and his dad decided to speak with the headmaster.

NOEL GORDON:My dad says to the headmaster, "This is a school for handicapped children." The headmaster said, "Yeah, but we don't like to use that word, we call them slow learners." At that point, my dad realised that, what sort of school it was, because they never told him before. But his hands were tied, he couldn't do nothing.

SHANEQUA PARIS:Noel's trip to the dentist had a devastating impact on his education. There was no evidence that Noel had a learning disability, and yet, he'd been sent to a school that specialised in just that. And his parents only realised the truth about the school when it was too late. But Noel was not the only one. The issue was widespread. Many other black children were being moved into schools for the so called educationally subnormal.

These schools had been set up for children with learning difficulties. However, black children of average and above-average intelligence were being placed there, and there were many ways this happened. IQ tests were often used to determine whether black children should be sent into ESN schools. This is a typical IQ test workbook. They were developed at the beginning of the 20th century and covered vocabulary and verbal reasoning. The tests were created to measure intelligence, as the questions supposedly didn't require any special knowledge. Psychologists administered the tests, and children who got a low score were sent to an ESN school.

The average score on the test was between 90 and 110, and one survey showed that newly arrived children from the West Indies were scoring an average of 76. But there was a simple reason for this. Differences in culture and language explained why the scores of so many newly arrived immigrant children were low. And a study proved that, once children had a chance to settle in, their IQ fell within the same average as white children.

But it wasn't just low scores on IQ tests that landed children in ESN schools. Negative stereotypes about black children were another reason, and one came up again and again. Bad behaviour. Anne-Marie Simpson was labelled as a bad child.

ANNE-MARIE SIMPSON:I was born in Jamaica in St. Elizabeth, and was raised by my grandmother up until the age of nine, when I came to England. The fairy tale was shattered. It was cold, damp. The person who I came to as my mother, we didn't have a relationship. It broke my heart, to be honest. So, yes, lost, lonely, disappointed. I realised that I couldn't keep up with my peers. Well, I was excluded from that school because I used to get myself into fights and subsequently ended up in a special needs school. No one's never thought of, "Well, hang on, Anne-Marie has missed out so many learning years, she would be struggling." But who was in my corner?

SHANEQUA PARIS:But there were adults at the time who had begun to suspect that children like Anne-Marie were placed in ESN schools for no legitimate reason. One of them was a youth worker called Bernard Coard. He had begun to realise that something was seriously wrong.

Bernard Coard could see what was happening, but he had no proof, so he decided to investigate, and he started in the library of the Institute of Education at London University. And it was there that he uncovered the data that revealed a scandal.

Bernard got his hands on a secret report from the Inner London Education Authority. It revealed that the government knew that black children were being wrongly placed in ESN schools in greater numbers than white children. The report categorically stated that they were not less intelligent. Bernard was outraged. Here was proof that the fears of so many black parents were real. With extensive research, he wrote an influential book.

BERNARD COARD:A black kid is four times more likely to be wrongly placed in an ESN school than a white kid. In other words, there were four times as many black children in ESN schools, who should not have been there, as there were white working-class kids, who also should not have been there. The ratio was four to one.

SHANEQUA PARIS:Bernard's book exposed the truth about the numbers of black children in ESN schools and hit back at the assumption that black children were innately less intelligent than white children.

BERNARD COARD:I was able to point out to the Caribbean community that those in authority were not just doing something scandalously wrong, more importantly, they knew it, and even more importantly, having known it, we're gonna do nothing about it.

SHANEQUA PARIS:Bernard's book would have a major impact. Six months after the book was published, the government agreed to use it in teacher training colleges and, in 1981, a law was passed that banned educationally subnormal as a category.

Today, mainstream schools in the UK are more diverse, and many black children have a great education. But, a recent government investigation showed that institutional racism is still leading to discrimination against black children of Caribbean decent. Although ESN schools no longer exist, black children are still almost three times more likely to be permanently excluded than white children and taught in pupil referral units.

The scandal of educationally subnormal schools are a part of history. And though a lot of progress has been made, there's still a long way to go.

Video summary

This short film for secondary schools examines how black children in the 1960s and 1970s were disproportionately sent to schools for the so-called ‘educationally subnormal’.

Shanequa Paris tells the story of how a generation of West Indian migrants moved their families to the UK in hope of providing better opportunities and education for their children.

However, in a white-dominated country, where politics was becoming increasingly racialised, there was a question of how society saw these black British children.

Led by the influential theories of psychologists such as Hans Eysenck, who wrongly believed that black people were genetically less intelligent than white people, IQ tests were devised to target black children and move them to educationally subnormal schools (ESN schools) that taught only the basics of reading and writing.

Youth worker Bernard Coard wrote a book exposing the truth about the number of black children in ESN schools which led to the Government taking action, including banning the term 'educationally subnormal' as a category.

This BBC Teach film uses extracts from the BBC One documentary, 'Subnormal: A British Scandal'.

Due to the sensitive nature of the subject matter, we strongly advise teacher viewing before watching with your pupils. Careful preparation should be undertaken to prepare pupils before playing them this potentially traumatic and triggering story. The film includes descriptions of the racism black children and their families experienced in Britain, as well as the scientific racism that influenced policies such as segregating children in ESN schools.

You can also download these teaching guidelines, which were created for another BBC Teach series but contain relevant information for using videos in the classroom.

Teacher Notes

Before watching the film:

Prior to this lesson you may wish to introduce your students to some of the events mentioned in this short film to provide context. For example:

- The arrival of the Empire Windrush in 1948.

- The 1948 British Nationality Act, which conferred equal citizenship status to people in Britain and her colonies.

- The changing nature of migration (at first it was mostly young, single adults but over time more families and children moved to Britain from the Commonwealth).

- The discriminatory bussing of black and Asian students in the 1960s and 1970s in an attempt to disperse them.

During watching the film:

You may wish to pause the short film at certain points to check for understanding. Alternatively, you could wait until the end and pose questions such as:

- What were many black Caribbean parents hoping for their children?

- Why did the Department for Education recommend only 30% of pupils should come from an ‘immigrant background’ and what were the consequences of this recommendation?

- Why were children sent to ‘Educationally Subnormal Schools’?

- How was the West Indian community discriminated against by the education system?

- How did the black community respond to being let down by the education system?

- What was taught in Supplementary Schools?

- What is the situation today?

Following on:

You could ask students to summarise the key points of the video. This could be done in various different ways, through storyboarding or via bullet points. At KS4 this short film may serve as a case study in a lesson about West Indian migration to post-war Britain.

ESN teacher and activist, Bernard Coard features in the film. He wrote the seminal book ‘How the West Indian Child is made Educationally Sub-Normal in the British School System’ in 1971. One option is to use the film as part of a lesson looking at why Bernard Coard wrote the book and what impact it had, with a focus on parental activism. A range of relevant primary source material exists. The George Padmore Institute has a selection of sources available on its website, such as letters about ‘How the West Indian Child is made Educationally Sub-Normal in the British School System’ and campaign leaflets.

If using this short film in citizenship or PSHE, you may wish to focus more on contemporary issues. The end of the video considers the educational experiences of students with black Caribbean heritage today. This could lead to a lesson about school exclusion and educational inequality. Another contemporary angle is that the recent Windrush scandal has primarily affected children who arrived in Britain in this period. You may wish to draw attention to this and use the film as an opportunity to explore what the Windrush scandal is, what caused it and how the government has responded.

This short film is suitable for teaching KS3 and KS4 students.

It could be used as part of citizenship or PSHE, when looking at how education has changed over time, or to spark discussion about educational inequality.

It could fit as part of a KS3 history curriculum when looking at ‘social, cultural and technological change in post-war British society.’ For example, it could be integrated into an enquiry or scheme of work looking at migration to Britain or black British history.

At KS4, this short film could be used to illustrate the experiences and treatment of migrants to Britain after World War Two as part of the AQA ‘Empire, Migration and the People’ course, the OCR ‘Migrants to Britain’ course or the forthcoming Edexcel Migration course.

Useful follow-on content:

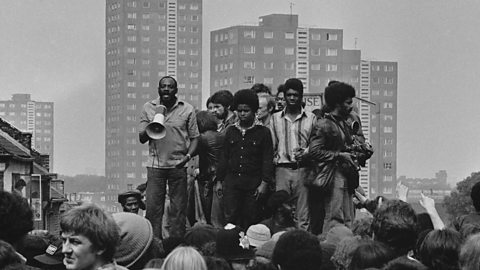

Black Power - A British Story of Resistance. video

This short film for secondary schools looks at the Black Power movement in the 1960s in the UK, surveying both the individuals and the cultural forces that defined the era.

Uprising. video

This short film for secondary schools looks at the New Cross house fire of 1981, and the protests, unrest and accusations of indifference that followed and defined race relations for a generation.

Educationally Subnormal Schools. video

Kenyah Sandy, who plays Kingsley Smith in Steve McQueen's Small Axe, tells the story of how hundreds of children were taken out of mainstream schools and sent to Educationally Subnormal Schools (ESN schools) in the 1970's.